Remote Chilliwack drug treatment facility may be cheaper than prison but neighbours pay a price

VisionQuest at The Creek is a treatment centre up the Chilliwack River Valley with zero security where prolific offenders, including pedophiles, often walk away

This is both parts of a two-part series that appeared in the August 13, 2015 and August 20, 2015 editions of The Chilliwack Times. VisionQuest is long closed but the location is still a Christian treatment centre, now operated by Joshua House out of Abbotsford as Phase 1 of a three-phase program for men overcoming drug/alcohol addictions – PJH, Jan. 8, 2026

August 13, 2015

As the high summer sun begins to dip lower in the sky and the crisp evenings of fall set in, Jodie Crawford and her husband Roy Wilson like to go camping and hunting in the Chilliwack River Valley.

On one of those trips in October 2014 a visitor stopped at their camp near the Riverside Recreation site at about the 30-kilometre mark – not far from the couple’s home just south of Tamihi Rapids in the valley.

The man got out of his GMC SUV to have a chat about a nearby drug and alcohol facility, a place they didn’t even know existed.

“He said we ‘need to turn our music down because there are pedophiles and sexual offenders there and they have a tendency of wandering away,’” Crawford said.

“Who the hell is up there?” they asked.

The “there” in question is VisionQuest at The Creek, a treatment facility for prolific offenders, located on a 32.5-acre site way up Chilliwack Lake Road.

Crawford and valley residents aren’t the only ones asking just what type of offenders are housed at The Creek, and what is being done about assuring the community they will be protected from the “clients” who so frequently make a run for it.

Elected officials and senior staff at the City of Chilliwack and the Fraser Valley Regional District (FVRD) are extremely concerned about public safety and the uncertainty of who is at The Creek.

Even Superintendent Deanne Burleigh, officer in charge of the Upper Fraser Valley Regional RCMP detachment, can’t say.

“Do I know who is at VisionQuest?” Burleigh said in a recent interview. “Only after someone walks away and I have arrested them. . . . No, I don’t know who is at VisionQuest.”

RCMP called every other day

Who is up there now, and who has been up there in the past, at this remote location 36 kilometres up the Valley living in cabins on a picturesque site along the Chilliwack River is, quite simply, a stream of criminal offenders with no fewer than 30 convictions on their records.

Delta-based non-profit VisionQuest Recovery Society opened VisionQuest at The Creek at 60550 Chilliwack Lake Rd., in 2013.

Before it was The Creek, the location was the site of the Stehiyaq Healing and Wellness Village for aboriginal youth, which was provincially funded to the tune of $1.5 million, and which closed down in September 2011.

Long a site known by the local Sto:lo people for healing, the question could be asked, who cares if there are prolific offenders at The Creek? After all, Ford Mountain Correctional Centre is just seven kilometres down the road.

The difference, and the source of much consternation at city hall, is that at The Creek there is no security. Clients are “sentenced” to attend the rehab programs at The Creek in lieu of jail time, which means to walk away may be a criminal breach.

But it happens all the time. In February of this year, 29-year-old Robert Ross Winston took off from The Creek and police asked the public for help to apprehend him. Then on June 9, Christopher Chubb went with VisionQuest staff to attend court in Chilliwack. In a brief chat with this reporter a month later, the 33-year-old said he thought he was late for his court appearance and a warrant had been issued. So he bolted.

About once a week, on average, a prolific offender such as Winston or Chubb walks away from The Creek, and that number pales in comparison to the number of RCMP calls for service to the facility.

In its first nine months in existence, April to December 2013, the RCMP had 111 files connected to The Creek. In 2014, there were 221 calls for service and by June of this year, Burleigh said there were already 100 calls. That’s 432 RCMP files over 27 months, or 16 per month.

Every other day, a Mountie, and sometimes more than one, is called off the streets of Chilliwack into FVRD Area E to deal with a problem at The Creek.

Sexual offenders are permitted

Chilliwack city councillor Jason Lum has had The Creek on his radar from back when he was chair of the city’s Public Safety Advisory Committee. Lum is no longer chair, but he is unrelenting in his conviction that the public safety danger of the facility is too much, and changes need to be made.

“There are literally hundreds of calls that are generated from this one facility,” Lum said in an interview. “Everybody has been very patient but it’s running low.”

If prolific offenders are walking away from The Creek, Lum wants to know if those offenders are in for petty crimes or do they have convictions for violent and/or sexual incidents. He says the city has always been told VisionQuest does not take sexual offenders but even the facility’s managers don’t have access to criminal records. It is provincial court judges that send offenders to VisionQuest, and the clients have to agree to go. (Part of that means clients sign over their social assistance cheques, which is the main source of their funding. The VisionQuest Society brags that it costs about $207 a day to keep a prisoner in a provincial jail and they do it for $30.90 a day.)

But it is only a client’s latest conviction that is made available to VisionQuest. If a prolific offender has 30 convictions, there are 29 the folks who run The Creek don’t know about.

So do they accept sexual offenders?

“There have been several cases of clients at VisionQuest with very concerning histories of sexual offences,” Burleigh told Mayor Sharon Gaetz in a May 21, 2015 letter to the city in response to questions about The Creek.

In February of this year, for example, a client “with a long criminal history including sexual offences was reported AWOL from VisionQuest.” It took a Lower Mainland-wide effort to re-arrest him.

Then in March and again in May, another client with violent and sexual offence history took off from The Creek.

Burleigh recounted a third incident when a client jumped from a VisionQuest transport vehicle and was at large. He ended up in a bad spot: At the military range in the Chilliwack River Valley while an RCMP carbine course was underway.

“He has a history of sexual offences.”

Drugs don’t just drive the system

Chilliwack-Hope MLA Laurie Throness is a big supporter of VisionQuest at The Creek, both as a much-needed recovery facility in the big picture, but also as a constituent in his riding.

“I’ve toured VisionQuest a couple of times,” he said. “They do good work. Everyone I’ve talked to reports they do good work and they achieve really good lasting results.”

Throness is also Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Justice and recently he penned a report entitled Standing Against Violence: A Safety Review of BC Corrections.

The mission statement that drives the work of recovery facilities such as VisionQuest is essential to getting to the root cause of crime in British Columbia, according to Throness. Statistics Canada reported in 2012 that 92 per cent of those in correctional facilities in five provinces needed assistance with substance abuse.

“As one [corrections official] put it,” Throness wrote in his report. “Drugs don’t drive the system. They are the system.’”

And while Throness is keenly aware of concerns from the city and the FVRD, he said the concern over walkaways might be misplaced.

“Sometimes with criminal justice there’s more of a perception than a reality, and I think there is a perception of danger to the public from VisionQuest that may not be warranted,” Throness said.

He added that those who walk away don’t linger in the valley, they are often picked up by friends and are gone to other communities and a warrant is issued for their arrest.

“If they leave and they don’t come back, they go to jail.”

But sometimes they get a second chance. Remember Christopher Chubb mentioned earlier? He breached his conditions by taking off from VisionQuest staff on June 9, 2015. He was re-arrested in July and then later he walked away again.

The Creek’s executive director Jim O’Rourke told this reporter that as for Chubb, “we are kind of done with him.”

After Chubb walked away for the second time, he went back to the coast. He is currently in custody facing a new charge from an incident on July 28, 2015, in Vancouver: Sexual assault.

It’s cases like this that only heighten concern for people such as Crawford and her family.

“We have small children and we like to go camping and they are wandering through the forest,” Crawford said. “Seriously, this isn’t fair for our neighbourhood. We are pretty rural out here but at lease we know with Ford Mountain they are contained. Who knows what kind of criminals are up at this VisionQuest.”

◗ See Part Two of The Long Road to Recovery where I took a tour of the facility, talked in detail about the program with executive director Jim O’Rourke and the facility’s spiritual advisors, and I look Throness and his passion to solve the criminal justice system’s biggest problem: The revolving door, known as the rate of recidivism.

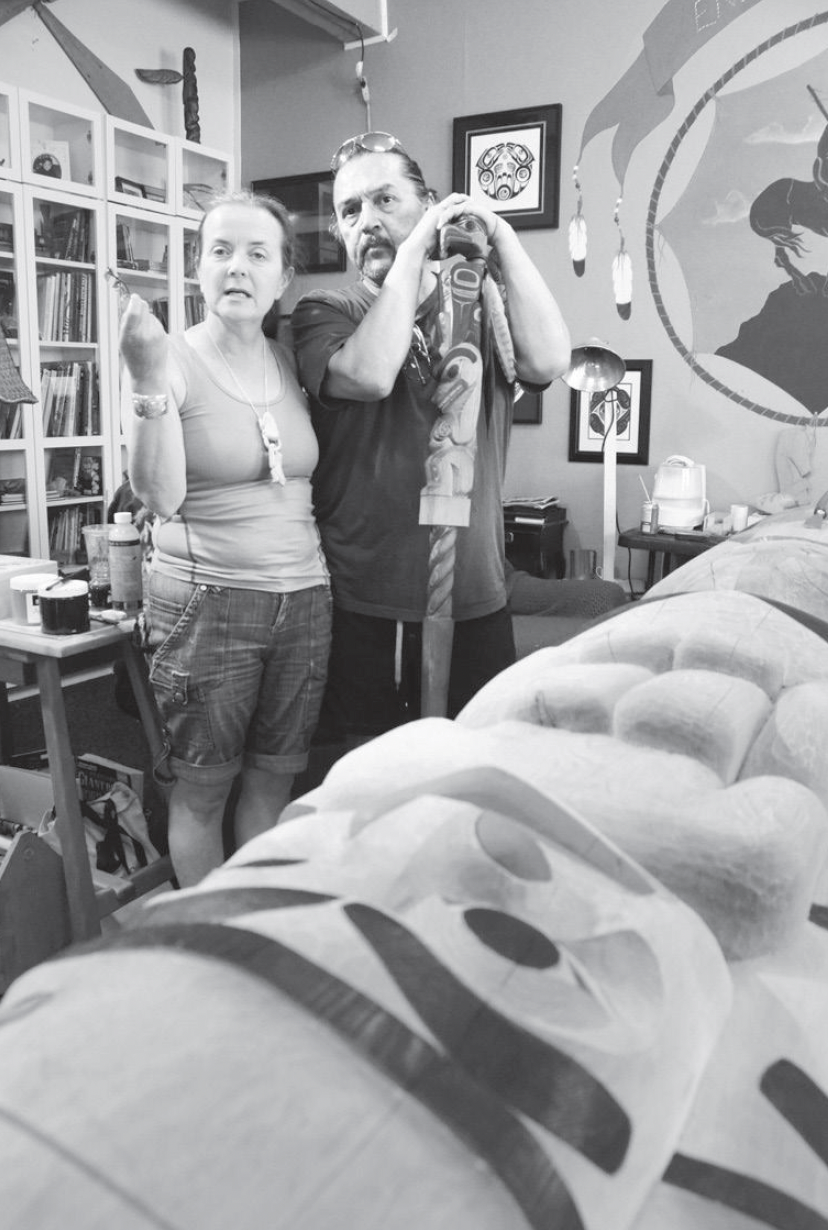

Page 1 of the Aug. 13, 2025, Chilliwack Times (left), 'Mama' and 'Papa" (centre) the spiritual advisors at VisionQuest, and executive director Jim O’Rourke. (Chilliwack Times image/ Paul Henderson photos)

◗ Part Two of a two-part series on VisionQuest that originally appeared in the August 13 & 20, 2015 editions of The Chilliwack Times

Visitors to a drug and alcohol treatment facility in the Chilliwack River Valley arrive to no gatehouse, no gate and not even a fence. The first person encountered at VisionQuest at The Creek is as likely to be a client of the facility as a staff member.

On a sunny summer day, some of the men — all of whom are prolific offenders — toss around a football, sit around and chat or simply walk around the large property.

What has caused great consternation at city hall, at the Fraser Valley Regional District (FVRD) and among some Chilliwack River Valley residents, is the fact that there is no supervision and no security at a place that sometimes houses sexual offenders, violent offenders and criminals with gang affiliations.

As this reporter arrived at the facility a tour was provided by site manager Allen Klassen. Klassen not only works at The Creek, he, like all employees, is a former client.

“I was a pretty functional addict,” he said. “I was smarter than everybody so I got away with stuff so I probably spent a lot less time in jail than a lot of these guys. But after 30 years you get stupider and crazier.”

On July 29, 2013 Klassen got particularly “crazy” while high on crystal meth in New Westminster. He had a knife and police reported he attacked two people on the street before fleeing into one victim’s house.

“I was in full psychotic mode when I was arrested. So much so they brought out the tactical squad and I couldn’t have even told you they were there.”

But Klassen got help at VisionQuest, he got clean and now he helps other men do the same thing.

Changing lives

Touring the seven cabins of VisionQuest I came across men who were writing, reading, contemplating. Some of then even self-admitted to the treatment program.

“I’m just taking each day as it comes,” one self-admitted client said.

“It’s working for me,” said another. “Just gives me time to explore myself, I guess. To put your head on right.”

Klassen said the goal is to tackle the drug addictions early to stop the revolving door.

“We are trying to help the guys that haven’t been in jail for years, try to nip it in the bud so they don’t have to go through what we went through for 20 or 30 years.”

Over at another building are the spiritual advisors known to the men only as Mama and Papa. Papa carves a large totem pole and talks about how many of the men he helps have been given up on by society.

“They come here completely broken,” Papa said. “Some guys feel like they are here as a get-out- of-jail free card and then they turn their lives around.

“We need a place like this.”

Practical and laudable goal

Ninety per cent of offenders serving sentences in provincial and federal institutions are addicted to something, be it alcohol or crystal meth or heroin or oxycontin or other substances. Much of the criminality that occurs on the streets of Chilliwack and across British Columbia stems from these addictions and can be directly attributed to those habits.

So getting at the root cause by tackling the addictions of the Lower Mainland’s most prolific offenders is a solution that is sensible, compassionate, practical and will save taxpayers money, according to Laurie Throness who is MLA for Chilliwack-Hope but also Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Justice.

“If we want to stop the revolving door that results from addiction then we need to provide people with long-term treatment that leads to recovery,” he said.

Stopping crime before it happens is the practical goal of drug treatment and keeping people out of prison saves taxpayers money. There is a further saving at VisionQuest as it costs just $30.90 a day to house one client while it costs more than $200 a day in a provincial correctional facility.

“We spend over $1 billion a year in our justice system,” Throness said. “If we could reduce this by reducing addiction to drugs and alcohol then that would be a huge long-term savings.”

Throness added there is a positive “cost” as well, as recovered addicts become contributing citizens.

His position on the direct and indirect cost savings of a place like VisionQuest echoes the sentiments of the facility’s executive director, Jim O’Rourke. “What we do is we dust you off and we teach you to become a taxpayer,” he said during an interview in his office at the facility. “It doesn’t work for everybody, nothing does.”

O’Rourke is firm about the mission of VisionQuest and unapologetic about the side effects.

“The philosophy of VisionQuest is this is their one shot of getting better and if they don’t get better the judge has no problem throwing the book at them. This is kind of like last chance for romance. . . . I’m a pretty good bang for your buck

and I give you back a taxpayer at the end of the day.”

O’Rourke, as with all the employees who work at VisionQuest, is a recovering addict and an ex-con himself.

“My convictions were for importation of narcotics and my affiliations were gangs,” he said. “I was naughty. But I haven’t

broken the law in 24 years and I’m 24 years clean.”

Summer and the runners

While tackling the rate of recidivism, known as the revolving door, is the laudable goal of VisionQuest, one that Throness backs 100 per cent, the City of Chilliwack and the FVRD have grave concerns about sexual offenders, violent offenders and even men with gang affiliations living unsupervised in seven cabins on a property 36 kilometres up the Chilliwack River Valley.

“There are literally hundreds of [RCMP] calls generated from this one facility,” Coun. Jason Lum said. “The crux of our concern is how are you giving us the assurance that you are going to fix the problem?

How are you going to solve the problem of the walkaways? You say that you don’t allow sexual offenders in your location but . . . the policy side may not be matching up with reality.”

Chilliwack RCMP Superintendent Deanne Burleigh confirms there have been a number of cases when her officers have re-arrested VisionQuest walkaways who have a history of sexual offences. Burleigh also provided statistics to show that there were 432 RCMP files connected to this one facility in the first 27 months it existed up to June 2015. That is 16 per month, or every other day that an officer is called to deal with a problem at VisionQuest.

Usually it’s what is referred to as a “runner.”

During a recent visit, both Klassen and O’Rourke didn’t hide the fact that clients take off all the time. Five minutes into a tour, Klassen was asked how many clients were at the facility.

“About 40, less, it’s kind of low right now,” he said. “Summer brings on runners.... It’s a bit of a run back to town and during the winter you don’t get the traffic so you can’t hitchhike.”

O’Rourke confirmed the number that July day this reporter visited was 38 at a facility with a capacity for 70.

“In summertime it’s easier to sleep in the park,” O’Rourke said. “In September we’ll be full, soon as it starts to rain.”

Valley resident Jodie Crawford said she and her family camp in the area, and she is concerned that sexual offenders could we walking loose.

O’Rourke is unapologetic.

“We’ve got campers in the valley, guys growing pot down this road, gang members living on the street shooting it up half the night. My guys here are the least of your problems.”

Throness agrees and while he is not happy about the RCMP call volume (and he thinks he has a solution) he said there are nearly 100 drug treatment facilities in B.C. and they are integral as part of the long-term solution to the high rate of recidivism.

“We cannot have 98 communities saying ‘not here.’ These people are here, they are everywhere in B.C. and we have to deal with this problem. VisionQuest is a very isolated place. It’s out of cell range. It is a long way from town. It is a good place to isolate men and treat them.”

A possible solution

City hall and the RCMP have argued that criminal record checks of clients at VisionQuest would go a long way to allay concerns, as long as it meant ensuring sexual and violent offenders were not admitted.

In a May 2015 memo to Mayor Sharon Gaetz about VisionQuest, Burleigh said she “has suggested . . . that it would be beneficial to have clients agree to a criminal record check as part of their acceptance into the VisionQuest program and as part of the decision-making process for acceptance.”

Both Throness and O’Rourke said this creates privacy issues, but Lum points out that anyone can submit to a criminal record check so why not make clients do so? Throness said he has been working on a plan that will hopefully get at concerns from the city and the FVRD. That is to work with probation officers who know the entire criminal record of every inmate, and they can determine if someone is unsuitable to live at a facility with zero security.

“We think that will result in greater public safety,” he said.

Addicts, drugs and no security

Both city hall and the RCMP are acutely aware of another issue at VisionQuest, and that is drugs being smuggled in. There is no security at the facility and visitors are not searched when they visit.

O’Rourke said he drug tests his clients every week and if they “test hot,” they are kicked out, but many remain skeptical about this and this reporter has heard numerous anecdotes from family members of clients and from inside the criminal justice system that drugs are rife at VisionQuest.

A source who asked not to be named told this reporter he thinks his addicted nephew did more drugs inside VisionQuest than on the outside.

“He was not going to be able to get off drugs in there,” he said. “That place is so tainted with drugs it’s unbelievable.”

One thing all parties agree on is that the system is not perfect, not by a long shot. Where they disagree is that supporters of VisionQuest think it’s helping some men recover, reduce recidivism and save money, while critics say the risk to public safety is too great.

-30-

Want to support independent journalism?

Consider becoming a paid subscriber or make a one-time donation so I can continue this work.

Paul J. Henderson

pauljhenderson@gmail.com

facebook.com/PaulJHendersonJournalist

instagram.com/wordsarehard_pjh

x.com/PeeJayAitch

wordsarehard-pjh.bsky.social