Fraser Valley music teacher deemed a ‘high risk for stalking’ applies to revoke guilty pleas for criminal harassment

Bevin van Liempt's relentless pursuit of teenage girls led to two convictions, multiple breach charges, and a summer behind bars in advanced of scheduled sentencing

September 4, 2025

Just when his victims likely thought it was almost over, Fraser Valley music teacher Bevin van Liempt – deemed a “high risk for stalking” in a psychological report – is applying to revoke his guilty pleas on two separate criminal harassment files today (Sept. 4, 2025), the day of his scheduled sentencing hearing.

Van Liempt’s relentless romantic pursuit of two 17-year-old female music students led to two convictions of criminal harassment followed by two allegations of breaching release conditions.

While out of custody in July, he allegedly contacted a third female in violation of a ban on using social media. He also shared the names of his victims with an Abbotsford News reporter, which was determined to be a violation of the ban on sharing his victims’ identities.

Having already twice been released on bail to live with his mother, Chilliwack Symphony Orchestra conductor Paula DeWit, and allegedly violating release conditions, Crown applied to have his bail revoked for the above. Since his release plan was yet again to live with his mother, Crown counsel Dorothy Tsui addressed her lack of an ability or interest in restraining his stalking.

“Mr. Van Liempt’s mother didn’t see it as a problem that her 33-year-old wanted to ask a 17-year-old out,” Tsui said at the hearing in June. “She blames the 17-year-old. She saw him in lessons and thought she was flirting with him.”

In deciding to revoke the bail, the judge also addressed DeWit's “failure to recognize his concerning behaviour or, if she can, she was unwilling.”

Because of this, on July 24 his bail was revoked and he spent the rest of that month and August behind bars, the judge making it clear from a psychological report that van Liempt is a “high risk for stalking” and a “danger to public safety.”

On Sept. 4 in court, van Liempt applied to revoke his guilty pleas, at least in part because he claimed he thought there was an agreement with Crown counsel that if he pleaded guilty, they would recommend a conditional discharge. (Note: An earlier version of this suggested van Liempt was using Section 7 directly to have his guilty pleas withdrawn but that's not accurate. He is using Section 7 for a different application regarding his treatment. See below for a detailed look at possible Section 7 arguments regarding plea withdrawal.)

Crown counsel James Barbour was having none of it, calling van Liempt's claim regarding a possible sentencing deal in exchange for a guilty plea “unrealistic and concocted.”

He also said van Liempt's application was meant to frustrate the criminal justice system, torment and cause distress to his victims.

Finch suggested that van Liempt's notion about a sentencing deal wasn't concocted but was simply a mistake. When there are matters with such a high stakes such as guilt of a crime, pleas to the court have to be voluntary, informed, and unequivocal. Finch focused on the requirement for informed decision-making as in, the plea was voluntary, but was based on van Liempt's mistaken understanding that if he pleaded guilty, Crown would recommend a conditional discharge.

Finch admitted what Barbour had said, that no such agreement was in place, but van Liempt thought otherwise.

"This man has not entered a guilty plea unless he was, on a high level of certainty, getting a conditional discharge," Finch said.

A plea can be revoked if an accused doesn’t understand the nature of the charge or the consequences of pleading guilty because of, for example, language barriers, mental health issues, ineffective legal advice. One of the principles of fundamental justice is that decisions with high stakes must be voluntary, informed, and unequivocal.

Prior to having his bail revoked on July 24, van Liempt had already spent close to 100 days in pretrial custody. That number was approximately 150 by Sept. 4. For first offences such as non-violent criminal harassment, it is unlikely any judge would sentence him to anything more than time served with probation. He would, however, still have a criminal conviction.

Van Liempt also faces a trial date in October for one of his original breach charges.

Van Liempt's lawyer Martin Finch repeatedly painted the 33-year-old as a victim, a teacher turned "pariah in the musical [sic] community," directly blaming Something Worth Reading, while using pejorative language.

“A great deal of commenting was made by readers of this particular quasi-news presentation,” Finch said in court in July. “The upshot of it was, it escalated in rancour and negative views he has had to live with.”

Finch putting the blame for van Liempt's bad treatment in the community is somewhat backwards. The only reason the case received public attention in the first place is because of the community. More than two dozen members involved in classical music in the Fraser Valley who have come in contact with van Liempt sent messages to this reporter expressing thanks, encouragement, while providing background and context for the many years of behaviour coming to light.

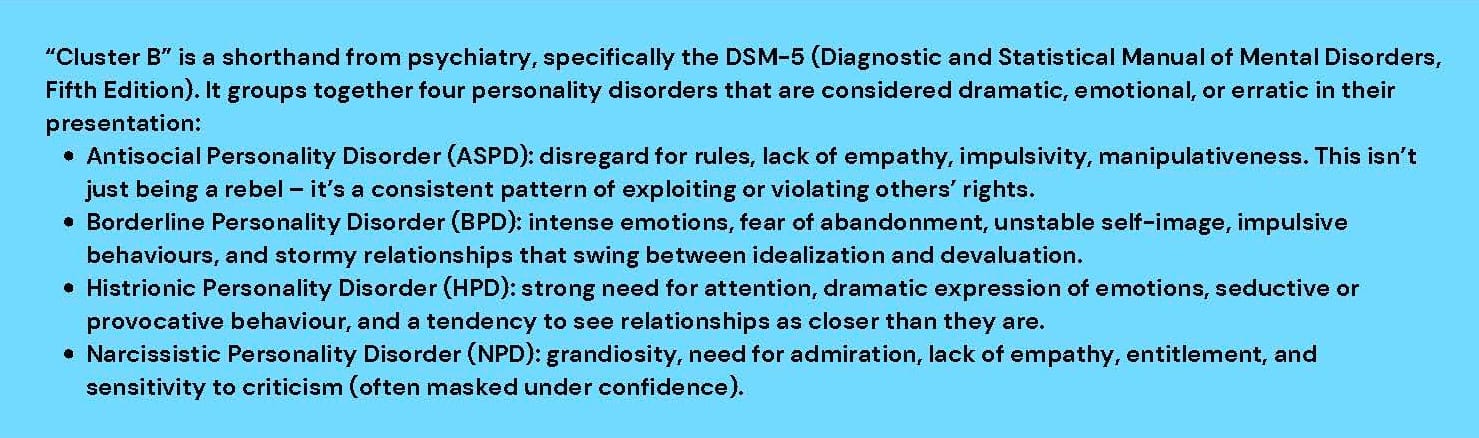

In revoking bail on all four informations before the court in June, the judge read from a psychological report that determined van Liempt represented an imminent and high risk for stalking, that he is a danger to public safety if released, and the plan to live with his mother “will not attenuate that risk.” The interviewer also diagnosed van Liempt with "Cluster B Traits" in that same pre-sentence report, and that he had no remorse and no insight into his actions.

His case in Abbotsford provincial court ran most of Thursday (Sept. 4, 2025) and was set to continue Friday afternoon.

Section 7 of the Charter and a guilty plea

How could an accused use Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms to revoke guilty pleas? A guilty plea is not a formality, it is waiving of fundamental rights in Canadian criminal law. Section 7 of the Charter says: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.”

That’s the artillery an accused could try to bring to bear if they later regret or challenge a guilty plea. Here is a couple of ways it might work:

1. Liberty

When an accused pleads guilty, that will likely lead to a conviction and a loss of liberty, such as prison or probation with conditions. Since liberty is directly at stake, Section 7 is in play. If the state is depriving you of your liberty because of a guilty plea that you regret, it could be argued that justice is not being respected. Pleading guilty, however, is waiving of rights, including Charter-protected rights.

2. Voluntariness

One of those principles of fundamental justice is that decisions with high stakes must be voluntary, informed, and unequivocal. A Section 7 argument could claim:

- The plea wasn’t truly voluntary (e.g., entered under duress, pressure, or coercion). There was a period of time when van Liempt did not have a lawyer, so Finch might hang his hat on this.

- The accused didn’t understand the nature of the charge or the consequences of pleading guilty because of, for example, language barriers, mental health issues, ineffective legal advice.

- The plea was equivocal meaning the accused expressed doubt or protested innocence at the same time. Van Liempt could use this as he expressed absolute innocence for a considerable amount of time, including trial proceedings until he suddenly pleaded guilty.

The 2018 Supreme Court of Canada case of R. v. Wong is an important precedent-setting case on guilty pleas and the Charter. Mr. Wong pled guilty to a criminal charge without knowing that a conviction would make him automatically deportable because he wasn’t a Canadian citizen. The Court held that this lack of knowledge went to the informed part of a valid plea. Section 7 was engaged because his liberty was at stake, and a plea entered without proper understanding was inconsistent with fundamental justice.

The Court didn’t say every misunderstanding automatically invalidates a plea, but it laid out the test: an accused has to show there was a reasonable possibility they would have proceeded differently if properly informed.

3. Miscarriage of justice

Canadian courts are already cautious with guilty pleas. Section 7 can reinforce an application to withdraw a plea by framing it as a constitutional breach rather than just a procedural hiccup. For example, if new evidence shows factual innocence, Section 7 could be invoked to argue it’s fundamentally unjust to let the guilty plea stand.

4. Remedy

The remedy under Section 24(1) of the Charter could be withdrawal of the guilty plea, sending the matter back to trial. That’s not guaranteed, it depends on whether or not there was real prejudice or injustice, but Section 7 provides the constitutional muscle behind the argument.

-30-

Want to support independent journalism?

Consider becoming a paid subscriber or make a one-time donation so I can continue this work.

Paul J. Henderson

pauljhenderson@gmail.com

facebook.com/PaulJHendersonJournalist

instagram.com/wordsarehard_pjh

x.com/PeeJayAitch

wordsarehard-pjh.bsky.social